1861-1862

After the second wave of secession took Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina out of the Union, both Unionists and Confederates focused their attention on the border slave states of Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware. Confederates did not contest Delaware, which had few slaves and strong economic ties to the North. The loyalties of the rest of the border South were not clear. Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri all had significant secessionist populations and were especially critical to the outcome of the conflict. Abraham Lincoln famously quipped “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.” Lincoln and his military advisors realized that the loss of the border states could mean a significant decrease in Union resources and threaten the capital in Washington. Consequently, Lincoln hoped to foster loyalty among their citizens, so that Union forces could minimize their occupation in the regions and deploy soldiers elsewhere. Secessionists attempted to claim the border states for the Confederacy, but the Union army helped to keep the strategically important Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri (as well as Delaware) in the Union. These border states witnessed the first major military maneuvers of the war.[1]

Some historians speculate that had the Confederacy been able to count the border South in its column, that Confederates would have been able to outlast the Union and win the war. The three states would have added 45% to the Confederacy’s white population, 80% to its manufacturing capacity, and 40% to its supply of draft animals. The border states contributed 200,000 men to the Union army. Another 100,000 men from the upper Confederacy enlisted in the Union army. This totaled to approximately 300,000 men from the slave states in the Union army. If the border states had contributed soldiers in proportion to its population to the Confederate army, the Confederate ranks would have increased by another 250,000 men. These border states also contained geographical advantages that the North wanted. The Cumberland and Tennessee rivers flowed from Ohio through Kentucky and into Tennessee and northern Alabama. Kentucky was therefore a crucial state for the North to hold. Maryland was even more important, containing as it did the northern capital. We often understand the story of the border states as background information about how the different states arrayed themselves before the war began with the first battle. This slights the importance of the fight over the border South. The loss of the border slave South means that before what is considered the first major battle of the Civil War, the First Battle of Manassas, the Confederacy had already lost much of its resources and manpower and given the Union strategic advantages.[2]

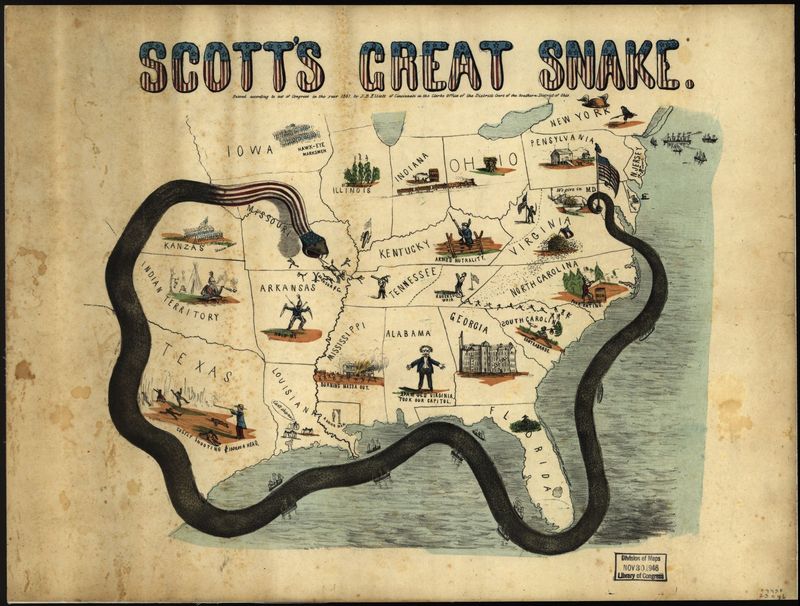

The Union adopted a logistic strategy of diminishing Confederate armies by reducing their base of supply. (Logistics here refer to the supply of an army.) This strategy was designed to deprive the Confederate armies of food, production, and manpower. The so-called anaconda plan was a version of this. Shortly after Lincoln’s call for troops, the Union adopted General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan to suppress the rebellion. This strategy intended to strangle the Confederacy by cutting off access to coastal ports and inland waterways via a naval blockade, while ground troops entered the interior. Like an anaconda snake, they planned to surround and squeeze the Confederacy. Scott warned that if the Union had to “conquer the seceding States by invading armies … [the] waste of human life” would be “enormous” and “the destruction of life and property on the other side would be frightful.” Instead, Scott recommended a naval blockade of the South combined with a federal presence on major rivers, including the Mississippi. Scott reasoned that the blockade would limit the South’s ability to wage war and eventually force the Confederacy to surrender. He hoped this would bring the war to an end with relatively little fighting and bloodshed.[3]

The northern public wanted to see action. They expected a dramatic and decisive battle, one that would annihilate the Confederate army and end the war. The northern general public thought that the path to victory led toward Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, which held great symbolic value. Most Union generals knew that the public demanded great victories on the battlefield. At the same time, however, they understood that the defensive was stronger and that they therefore had limited opportunities to deplete Confederate armies through actual combat. As a consequence, Union generals sought to conquer Confederate territory as a means of weakening Confederate armies. Loss of territory deprived Confederate armies of the food produced in that area as well as much of the manpower of that area. Loss of territory also had a political significance as it would affect public opinion in both the North and the South as well as abroad. Increasing advances into Confederate territory would boost northern morale, weaken southern morale, and convince foreign powers not to intervene.

Union strategists also targeted public opinion. They hoped their occupation and raids into Confederate territory along with the capture of the Confederate capitol would convince the South to give up and would keep European powers from intervening. Foreign countries, primarily in Europe, watched the unfolding war with deep interest. The United States represented the greatest example of democratic thought and ideals at the time, and individuals from as far afield as Britain, France, Spain, Russia and beyond closely followed events across the Atlantic Ocean. If the democratic experiment within the United States failed, many democratic activists in Europe wondered what hope might exist for such experiments elsewhere. Conversely, those with close ties to the cotton industry earnestly watched in the spring of 1861. War meant the possibility of disruption to their cotton produced on the backs of enslaved labor, and disruption could have catastrophic ramifications in commercial and financial markets abroad.

Confederates adopted an offensive-defensive strategy. Confederate armies launched offensive movements against Union armies when circumstances looked promising. While these offensive movements consumed soldiers’ lives, they provided hope of eventual success for the Confederate people (even as they ultimately failed to convince European powers to intervene on behalf of the Confederacy). Commanders positioned armies in defensive posture over as much of the Confederacy as possible. In particular, Confederate leaders recognized that Richmond represented a fundamental target of Union forces. They took dramatic steps to keep the capital out of Union hands. Indeed, defending Richmond seemed at times the Confederacy’s primary goal. Confederates devoted more supplies and soldiers to campaigns in Virginia than to defending Confederate borders anywhere else. Some historians argue that the best chance for Confederate success was to adopt a strategy of deep withdrawals to avoid engagement and save manpower resources. This strategy, however, would not have met the approval of the Confederate people. Maintaining its territorial integrity was crucial for Confederate morale. Confederates hoped that the ability of the Confederacy to maintain its territorial integrity would also affect public opinion in the Union and abroad. They believed that successful resistance would convince the U.S. that the war would be too costly. Confederates also hoped that they could gain a swift victory through the intervention of foreign powers as France had done for the patriots in the American Revolution. Confederates predicted that Britain, cut off from southern cotton by the war, would intervene on behalf of the Confederacy, a strategy referred to as “King Cotton Diplomacy.”[4]

While Union and Confederate leaders pondered their strategies and sought to limit the impact of the war, black Americans quickly forced the issue of slavery. As early as 1861, black Americans implored the Lincoln administration to serve in the army and navy. Lincoln, who initially waged a limited war, believed that the presence of African American troops would threaten the loyalty of slaveholding border states and white volunteers who might refuse to serve alongside black men. However, army commanders could not ignore the growing populations of enslaved people who escaped to freedom behind Union army lines. These men and women took a proactive stance early in the war and forced the federal government to act. As the number of refugees ballooned, Lincoln and Congress found it harder to avoid the issue.

Fugitive slaves posed a dilemma for the Union military. Soldiers were forbidden to interfere with slavery or assist runaways, but many soldiers found such a policy unchristian. Even those indifferent to slavery were reluctant to turn away potential laborers or help the enemy by returning his property. Also, fugitive slaves could provide useful information on the local terrain and the movements of Confederate troops. Union officers became particularly reluctant to turn away fugitive slaves when Confederate commanders began forcing slaves to work on fortifications. Every slave who escaped to Union lines was a loss to the Confederate war effort.

In May 1861, General Benjamin F. Butler went over his superiors’ heads and began accepting fugitive slaves who came to Fortress Monroe in Virginia. In order to avoid the issue of the slaves’ freedom, Butler reasoned that runaway slaves were “contraband of war” and that he had as much a right to seize them as enemy horses or cannons. Later that summer Congress affirmed Butler’s policy in the First Confiscation Act in August 1861. The act left “contrabands,” as these runaways were called, in a state of limbo. Once a slave escaped to Union lines, the master’s claim was nullified. He or she was not, however, a free citizen of the United States. Runaways lived in “contraband camps,” where disease and malnutrition were rampant. The men were required to perform the drudgework of war: raising fortifications, cooking meals, and laying railroad tracks. Still, life as a contraband offered a potential path to freedom, and thousands of slaves seized the opportunity. Most white northerners hoped that the rebellion could be suppressed quickly and that the thorny problem of fugitive slaves would therefore not become a pressing issue.

Any hopes for a brief conflict, however, were eradicated three months after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter when Union and Confederate forces met at the Battle of Manassas in Virginia, in July 1861. While not particularly deadly, the Confederate victory proved that the Civil War would be long and costly. Furthermore, in response to the embarrassing Union rout, Lincoln removed Brigadier General Irvin McDowell of command and promoted Major General George B. McClellan to commander of the newly formed Army of the Potomac. For nearly a year after the First Battle of Manassas, the Eastern Theater remained relatively silent. Smaller engagements only resulted in a bloody stalemate.

The military remained quiet, but the same could not be said of Republicans in Washington. The absence of fractious, stalling southerners in Congress allowed Republicans to finally pass the Whig economic package, including the Homestead Act, the Land-Grant College Act (a.k.a. Morrill Act), and the Pacific Railroad Act. The federal government also began moving toward a more nationally controlled currency system (the greenback) and the creation of banks with national characteristics. Such acts proved instrumental in the expansion and evolution of the federal government, industry, and political parties in the war and postwar years. The Democratic Party, absent its southern leaders, divided into two camps. War Democrats largely stood behind President Lincoln. “Peace Democrats”—also known derogatorily as “Copperheads”—clashed frequently with both War Democrats and Republicans. Copperheads exploited public anti-war sentiment (often the result of a lost battle or mounting casualties) and tried to push President Lincoln to negotiate an immediate peace.

While Washington buzzed with political activity, military life filled with relative monotony punctuated by brief periods of horror. Daily life for a Civil War soldier was one of routine. A typical day began around 6am and involved drill, marching, lunch break, and more drilling followed by policing the camp. Weapon inspection and cleaning followed, perhaps one final drill, dinner, and taps around 9 or 9:30 pm. Soldiers in both armies grew weary of the routine. Picketing or foraging afforded welcome distractions to the monotony. While there were nurses, camp followers, and some women who disguised themselves as men, camp life was overwhelmingly male. Soldiers drank liquor, smoked tobacco, gambled, and swore. Social commentators feared that when these men returned home, with their hard-drinking and irreligious ways, all decency, faith, and temperance would depart. But not all methods of distraction were detrimental. Soldiers also organized debate societies, composed music, sang songs, wrestled, raced horses, boxed, and played sports. Neither side could consistently provide supplies for their soldiers. Supply shortages and poor sanitation were synonymous with Civil War armies. The close proximity of thousands of men bred disease. Lice were soldiers’ daily companions.

After an extensive delay on the part of Union commander George McClellan, his 120,000 man Army of the Potomac moved via ship to the peninsula between the York and James Rivers in Virginia. Rather than crossing overland via the former battlefield at Manassas Junction, McClellan attempted to swing around the Rebel forces and enter the capital of Richmond before they knew what hit them. McClellan, however, was an overly cautious man who consistently overestimated his adversaries’ numbers to his detriment. This cautious approach played into the Confederate favor on the outskirts of Richmond. Recently appointed commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Confederate General Robert E. Lee, forced McClellan to retreat from Richmond and his Peninsular Campaign became a tremendous failure.

The campaign did produce a landmark moment in naval warfare. The Union and Confederate navies coordinated with army movements around the many marine environments of the southern United States. Each navy employed the latest technology to outmatch the other. The Confederate Navy, led by Stephen Russell Mallory, had the unenviable task of constructing a fleet from scratch and trying to fend off a vastly better equipped Union Navy. Led by Gideon Welles of Connecticut, the Union Navy implemented General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan. The future of naval warfare emerged in the spring of 1862 as two “ironclad” warships fought to a duel at the Battle of Hampton Roads, Virginia, part of the Peninsular Campaign. The age of the wooden sail was gone and naval warfare would be fundamentally altered.

Union forces met with little success in the East, but the Western Theater provided hope for the United States. In February 1862, Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s capture of Confederate Forts Henry and Donelson along the Tennessee River marked the opening of the Western Theater. Fighting in the West greatly differed from that in the East. At the First Battle of Manassas, for example, two large armies fought for control of the nations’ capitals. In the West, Union and Confederate forces fought for control of the rivers, since the Mississippi River and its tributaries were a key tenet of the Union’s Anaconda Plan. One of the deadliest of these clashes occurred along the Tennessee River at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6 to 7, 1862. This battle, lasting only two days, was the costliest single battle in American history up to that time. The Union victory shocked both the Union and the Confederacy with approximately 23,000 casualties, a number that exceeded casualties from all of the United States’ previous wars combined. The subsequent capture of New Orleans by Union forces proved a decisive blow to the Confederacy and capped a Western Theater spring of success in 1862.

With Union victories in the West and stalemate in the East, Confederate President Jefferson Davis in the summer and fall of 1862 ordered coordinated military offenses into Kentucky, western Tennessee (which early on was invaded and occupied by Union forces), and Maryland. One of the main goals of these offensives was to undermine the northern will to fight and to secure foreign intervention. The Confederate offensives into Kentucky, western Tennessee, and Maryland did not help the Confederate cause. Confederates invaded Kentucky, but were driven back and never again threatened the state during the war. Confederates attempted to invade western Tennessee three times, but failed all three times. The Maryland offensive also did not achieve much for the Confederacy and its net effect was to damage the Confederacy as Lincoln used the campaign as the occasion to issue his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

The Union had slowly been shifting to a policy of emancipation. By the summer of 1862, the actions of black Americans pushed the Union away from the hands-off stance towards slavery that characterized initial presidential and congressional policy. Following up on the First Confiscation Act passed in August 1861, Congress abolished the institution of slavery in the District of Columbia in April 1862, ending a practice in the nation’s capital deemed shameful by Republican lawmakers, and passed the Second Confiscation Act in July 1862, effectively emancipating slaves who came under Union control. Such legislation led to even more escaped slaves making their way into Union lines and putting further pressure on the Lincoln administration to contend with the future of slavery. For his part, President Lincoln evolved in his thinking on the issue. By the summer of 1862, Lincoln first floated the idea of an Emancipation Proclamation to members of his Cabinet. By August 1862, he proposed the first iteration of the Emancipation Proclamation. While his cabinet supported such an idea, Secretary of State William Seward insisted that Lincoln wait for a “decisive” Union victory so as not to appear too desperate a measure on the part of a failing government.

This decisive moment that prompted the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation occurred in the fall of 1862 in the Maryland Campaign along Antietam creek. Emboldened by their success in the previous spring and summer, General Robert E. Lee planned to win a decisive victory in Union territory and end the war. He anticipated that taking the war to the North and forcing the North to suffer the ravages of war could prod the Union to sue for peace or convince foreign powers to recognize and support the Confederacy. He also expected that an invasion of the North would alleviate the stress on the Confederate homefront by allowing the Confederate army to subsist on northern soil. Once he invaded Maryland, Lee thought that General George B. McClellan’s notorious caution would give him plenty of time to forage on enemy territory. McClellan, however, began moving his army with unusual speed and accelerated once a subordinate fortuitously found Lee’s plans for the campaign (wrapped around a cigar). On September 17, 1862, Lee’s and McClellan’s forces collided at the Battle of Antietam near the town of Sharpsburg. Even though McClellan had Lee’s plans, he was not able to capitalize on them. Lee succeeded in fending off a series of poorly executed Union attacks, but he could not occupy Maryland, however, because he lacked adequate supply lines and ultimately he withdrew to Virginia. This battle was the first major battle of the Civil War to occur on Union soil, and it remains the bloodiest single day in American history with over 20,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing in just twelve hours. More Americans were killed at Antietam than the casualties from the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American War combined. Despite these deaths, the battle itself had been a tactical draw. The campaign, however, had strategic and political significance.

Lincoln seized on the Battle of Antietam, though certainly not a decisive Union victory in the tactical sense of casualty statistics, to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves in areas under Confederate control on January 1, 1863. However, Lincoln granted significant exemptions to the Emancipation Proclamation including the border states and parts of other states in the Confederacy. A far cry from a universal end to slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation nevertheless proved vital in solidifying the Union’s shift in war aims from one of Union to Emancipation. Framing it as a war measure, Lincoln and his Cabinet hoped that stripping the Confederacy of their labor force would not only debilitate the southern economy, but also weaken Confederate morale. Furthermore, the Battle of Antietam and the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation all but ensured that the Confederacy would not be recognized by European powers.

The point of the campaigns in the eastern theater in 1861 and 1862 was to menace the respective capitals, Richmond and Washington, just 100 miles apart. The Union hoped to protect Washington and to capture Richmond. The Confederacy aimed to threaten Washington and, more importantly, to protect Richmond. There were bright spots for the Confederacy in the east in the first two years of the war. The Confederacy successfully prevented the Union from capturing Richmond. But the war (which many had imagined would last only three months) still raged on, and the Confederate army (though they still protected their capital) did not succeed in eliminating the Union threat to Virginia. By 1862, events in the eastern theater seemed to be at a standstill. More alarming for the Confederacy, the Union achieved important successes in the western theater. Through a series of battles, the United States made progress in the goal of securing control over the waterways of the western Confederacy. By the end of 1862, the U.S. controlled much of the Mississippi river, with Vicksburg as the main holdout against complete Union navigation. The Union’s success in the struggle for the western rivers boosted northern morale while at the same time diminishing southern hopes for an early victory.

[1] Abraham Lincoln to Orville Browning, September 22, 1861, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.; William W. Freehling, The South vs. the South: How Anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the Course of the Civil War (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 47–82.

[2] William W. Freehling, The South vs. the South: How Anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the Course of the Civil War (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 47–82.

[3] Freehling, The South vs. the South, 7.

[4] Gary W Gallagher, “‘On Their Success Hang Momentous Interests’: Generals,” in Why the Confederacy Lost, ed. Gabor Boritt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 81–108.