Abolitionist Movement

As slavery became more and more entrenched across the American South, the opposition to the institution grew. Free blacks and slaves themselves had long opposed the institution. They first organized in opposition to the colonization movement, which sought to remove free blacks from the United States and resettle them in Africa. Some colonizationists opposed slavery, but either thought that blacks could not function as free citizens in the United States or that white prejudice would prevent them from doing so. Other colonizationists, however, favored the movement as a means to strengthen slavery by neutralizing free blacks—who encouraged slaves to rebel against their owners—as a threat. The colonization movement generated vocal opposition among free blacks. David Walker in his appeal to the “Coloured Citizens Of The World” argued that “America is more our country than it is the whites—we have enriched it with our blood and tears.” He asked, “will they drive us from our property and homes, which we have earned with our blood?” As an alternative to colonization, free blacks in the North called for the immediate end to the institution of slavery. They organized to promote abolition, forming abolitionist societies and establishing abolitionist publications. Freedom’s Journal, established by John Russwurm and Samuel Cornish in 1827, was the first instance in which black Americans used a serial publication to promote the abolition of slavery and the extension of racial equality. Black abolitionists believed that it was necessary to plead their own cause. Advocating on their own behalf for their freedom rather than waiting for whites to give them their freedom demonstrated that blacks were entitled—by their intellectual, moral, and political merits—to an equal share of freedom.[1]

Black support for the immediate abolition of slavery preceded white support for the immediate abolition of slavery. White support for emancipation prior to blacks’ public calls for abolition had been gradualist in nature. Blacks’ vocal denunciation of the colonization movement challenged white abolitionists to think in new ways. Free blacks, then, became the driving force behind the transformation of American abolitionism. The radicalization of the movement against slavery is typically dated to 1831 when William Lloyd Garrison, a white abolitionist, commenced publication of his antislavery newspaper, the Liberator. Garrison had supported colonization, but black arguments against colonization had ultimately convinced him to repudiate the movement. Thereafter, Garrison advocated immediate abolition with an uncompromising tone. In his inaugural issue of the Liberator, he announced: “Urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—and I will be heard.”

And the message that he wanted heard was that slavery was a moral evil and blight upon the nation. Abolitionist efforts by whites in the 1830s primarily relied upon what is called “moral suasion.” Garrison rejected involvement in politics, which he believed required unacceptable moral compromises as the price of success. Garrison and other white abolitionists appealed to individuals to cleanse themselves and their society of the sin of slavery.

A wave of religious revivals, called the Second Great Awakening, also contributed to this shift among whites toward immediatism. The Second Great Awakening involved a substantial theological critique of orthodox Calvinism, specifically the idea that individuals were predestined for either heaven or hell. Calvinism began to seem too pessimistic for many American Christians. Worshippers increasingly began to take responsibility for their own spiritual fates by embracing theologies that emphasized human action in effecting salvation. Religious leaders promoted a movement known as “perfectionism.” They encouraged followers to join reform movements and create God’s kingdom on earth. The idea of “disinterested benevolence” also turned many evangelicals toward reform. Preachers championing disinterested benevolence argued that true Christianity requires that a person give up love of self in favor of love of others. Though perfectionism and disinterested benevolence were the most prominent forces encouraging benevolent societies, some preachers achieved the same end in their advocacy of postmillennialism. In this worldview, Christ’s return was foretold to occur after humanity had enjoyed one thousand years’ peace, and it was the duty of converted Christians to improve the world around them in order to pave the way for Christ’s return. The revivalist doctrines of salvation, perfectionism, and disinterested benevolence prompted many evangelical reformers to develop social reform networks that sought to alleviate social ills and eradicate moral vice, such as slavery, but also alcoholism and women’s rights.

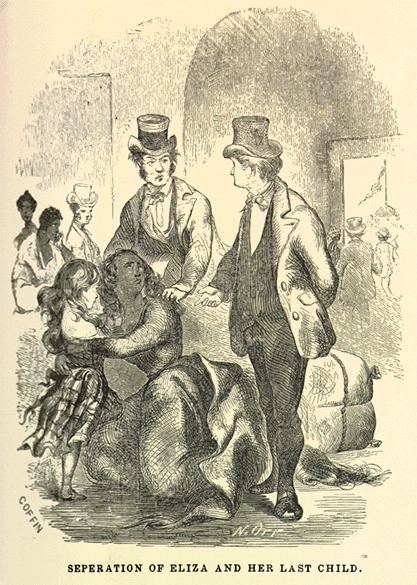

By the 1830s, a rising tide of anti-colonization sentiment among northern free blacks and a burgeoning commitment to social reform among white middle-class evangelicals prompted some whites to condemn slavery as the most God-defying sins and the most terrible blight on the moral virtue of the United States. Inspired by a strategy known as “moral suasion,” these abolitionists believed they could convince slaveholders to voluntarily free their slaves by appealing to their sense of Christian conscience. In order to accomplish their goals, abolitionists employed methods of outreach and agitation used in other social reform projects. Abolitionists established hundreds of antislavery societies and worked with long-standing associations of black activists to establish schools, churches, and voluntary associations. Harnessing the potential of steam-powered printing and mass communication, abolitionists blanketed the free states with pamphlets and antislavery newspapers. They blared their arguments from lyceum podiums and broadsides. Prominent individuals such as Wendell Phillips and Angelina Grimké saturated northern media with shame-inducing exposés of northern complicity in the return of fugitive slaves, and white reformers sentimentalized slave narratives that tugged at middle-class heartstrings. Abolitionists used the United States Postal Service in 1835 to inundate southern slaveholders’ with calls to emancipate their slaves in order to save their souls, and, in 1836, they prepared thousands of petitions for Congress as part of the “Great Petition Campaign.” In the six years from 1831 to 1837, abolitionist activities reached dizzying heights.

However, such efforts encountered fierce opposition, as most Americans did not share abolitionists’ cause. In fact, abolitionists remained a small, marginalized group detested by most white Americans in both the North and the South. Most whites attacked abolitionists as the harbingers of disunion, rabble-rousers who would stir up sectional tensions and thereby imperil the American experiment of self-government. [Footnote Varon here.] Particularly troubling to some observers was the public engagement of women as abolitionist speakers and activists. Fearful of disunion and outraged by the interracial and “promiscuous” nature of abolitionism, northern mobs smashed abolitionist printing presses and even killed a prominent antislavery newspaper editor named Elijah Lovejoy. White southerners, believing that abolitionists had incited Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831, aggressively purged antislavery dissent from the region. Violent harassment threatened abolitionists’ personal safety. In Congress, Whigs and Democrats joined forces in 1836 to pass an unprecedented restriction on freedom of political expression known as the “gag rule,” prohibiting all discussion of abolitionist petitions in the House of Representatives.

In the face of such substantial external opposition, abolitionism began to splinter. In 1839, an ideological schism shook the foundations of the movement. Moral suasionists, led most prominently by William Lloyd Garrison, felt that the United States Constitution was a fundamentally pro-slavery document and that the present political system was irredeemable. They dedicated their efforts exclusively towards persuading the public to redeem the nation by re-establishing it on antislavery grounds. However, many abolitionists, reeling from the level of entrenched opposition met in the 1830s, became disenchanted with moral suasion. Instead, they believed, abolition would have to be effected through existing political processes. So, in 1839, political abolitionists formed the Liberty Party under the leadership of James G. Birney. This new abolitionist party was predicated on the belief that the U.S. Constitution was actually an antislavery document that could be used to abolish the stain of slavery through the national political system. While moral suasionists continued to appeal to hearts and minds, and political abolitionists launched sustained campaigns to bring abolitionist agendas to the ballot box, the entrenched and violent opposition of slaveholders and their northern allies to their reform efforts encouraged abolitionists in the 1840s to turn to active resistance. Increasingly, for example, abolitionists focused on helping and protecting runaway slaves.

For all of the problems that abolitionism faced, the movement was far from a failure. The prominence of African Americans in abolitionist organizations offered a powerful, if imperfect, model of interracial coexistence. While immediatists always remained a minority, their efforts paved the way for the moderately antislavery Republican Party to gain traction in the years preceding the Civil War. It is hard to imagine that Abraham Lincoln could have become president in 1860 without the ground prepared by antislavery advocates and without the presence of radical abolitionists against whom he could be cast as a moderate alternative. Though it ultimately took a civil war to break the bonds of slavery in the United States, the evangelical moral compass of revivalist Protestantism brought public attention to abolition and inflamed sectional tensions.

[1] Timothy Patrick McCarthy, “‘To Plead Our Own Cause’: Black Print Culture and the Origins of American Abolitionism,” in Prophets of Protest: Reconsidering the History of American Abolitionism, ed. Timothy Patrick McCarthy and John Stauffer (New York: New Press, 2006), 114–44.