"Effect of John Brown’s Invasion"

By Micaela Magee

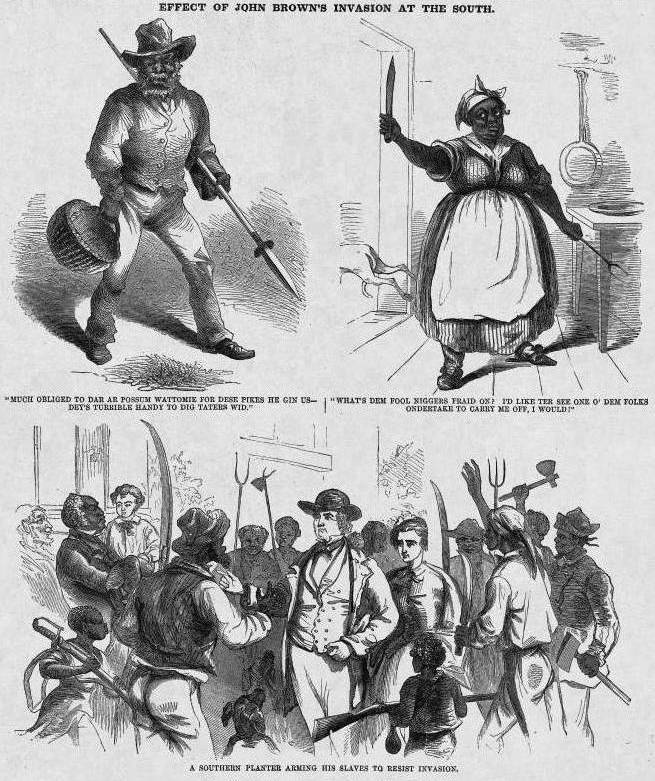

On the night of October 16, 1859, white abolitionist John Brown led an attempted slave revolt, including a raid on the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, lasting until October 18. A detachment of U.S. Marines led by Col. Robert E. Lee defeated Brown’s team of twenty-one men.[1] “Effect of John Brown’s Invasion at the South” is a reactionary cartoon to the events at Harpers Ferry. Harper’s Weekly published the critical cartoon on November 19, 1859, about a month after the events of the raid on Harpers Ferry. The cartoon's interpretation was in tune with both northern and southern ideologies and reactions to the event, which can be explained by the nonpartisan stance of Harper’s Weekly at this time.

The first image depicts a slave who has been given a pike by Brown. However, he finds it to be a very useful potato-farming tool, rather than a weapon as intended. In the bottom image, a southern plantation owner is actually giving his own slaves weapons in order to defend the plantation. The female slave in the top right corner is shown ready to fight anyone who threatens to take her away from her plantation. These images suggested that slaves remained loyal to their masters and mistresses and in this way mocked Brown's intention to incite slaves to rebellion as misguided.[2]

The editors of Harper’s Weekly aimed “to unite rather than to separate the views and feelings of the different sections of our common country.” The editors left “sectarian opinions in Religion, and sectional questions in Politics” to other venues. With readership in both the North and the South, Harper’s Weekly did not want to be perceived as a regional journal. The editors supported compromise on the slavery issue.[3]

Harper’s Weekly criticized the raid in its coverage. The journal identified the event as “the work of a half-crazed white, whose views and aims were, to say the least, extremely vague and indefinite.” The journal stated that although Brown intended a slave revolt, the slaves involved in the uprising were falsely implicated. The journal predicted that it would be a major blow to the Republican Party in the upcoming election and that it “will have cost the Republicans many thousand votes.” The author pointed out that even though the party had distanced itself from the raid, people would still associate the two. The editors of Harper’s Weekly attempted once again to bring the country together by stating, “For, whatever opinions a man may hold in reference to the slavery controversies which are agitated in this country, all are unanimous against any thing like compulsory emancipation and servile revolts.”[4]

In the North, people viewed the raid as unwise. Many, like the author of an article in the Ohio Enquirer, felt that it was a taste of what was to come and disagreed with bloodshed over the “Abolition doctrine.” They asked, do the majority in the free states even back up their “fanatical” views?[5] The Chicago Press and Tribune’s article, however, blamed southerners for the problems they brought upon themselves by “weakening the defenses of the institution by spreading it over an indefinite area” and spending so much energy opposing the abolitionists.[6] Meanwhile the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote about the shortcomings of Brown’s plan and his own admittance to them.[7]

In the South, the reaction was very much against Brown’s motives, not just his methods. They argued that the raid should not have been called an insurrection because the slaves who participated were forced into doing so.[8] Wilmington’s NC Daily Herald argued that the abolitionists’ foundational doctrine was called into question because the slaves were not willing to fight. “The negroes do not desire freedom. They had an opportunity -- a good one.”[9]

Because of the ambiguity of the cartoon, both northerners and southerners could read in the image the same general message they all agreed on and then in addition their own deeper messages that were more in alignment with their own political views. These political views, of course, centered around the nature of slavery and what should be done about the problems surrounding the institution. Northerners could read the cartoon as a criticism of the way in which John Brown sought to abolish slavery. They could agree with the foolishness of the planning, execution, and intent of the raid. Southerners, on the other hand, could read the cartoon as emphasizing the contentment of the slave population. White southerners believed that the slaves did not want to leave their masters and mistresses and those who did act up were doing so out of fear of white abolitionists. Harper’s Weekly only clearly sided with abolition after the war broke out.[10] In “Effect of John Brown’s Invasion at the South,” Harper’s Weekly tried to preserve what little unity that remained during the tumultuous pre-Civil War time period.

Endnotes

[1] Robert S. Wolff, “Harper’s Ferry, (West) Virginia,” in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, ed. David Stephen Heidler, Jeanne T. Heidler, and David J. Coles (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2000), 928.

[2] “Effect of John Brown’s Invasion at the South,” Harper’s Weekly, November 19, 1859.

[3] Eric Fettman, “Harper’s Weekly,” in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, ed. David Stephen Heidler, Jeanne T. Heidler, and David J. Coles (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2000), 931.

[4] “Insurrection at Harper’s Ferry,” Harper’s Weekly, October 29, 1859.

[5] "The First Battle of the 'Irrepressible Conflict,'" Ohio Enquirer, October 19, 1859.

[6] "The True Policy," Chicago Press and Tribune, October 22, 1859.

[7] "An Insurrection Without Negroes," Cincinnati Enquirer, December 4, 1859.

[8] "The True Lesson," New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 30, 1859.

[9] "A Misnomer," Wilmington, NC Daily Herald, October 26, 1859.

[10] Eric Fettman, “Harper’s Weekly,” in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, ed. David Stephen Heidler, Jeanne T. Heidler, and David J. Coles (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2000), 931.