Title

Creator

Description

Civil War legal codes define desertion as the deliberate abandonment of one’s military duty with the intention to remain absent. The earliest estimate of Confederate desertion comes from December 1862, when the fledgling army found several thousand of its soldiers unaccountably missing. By war’s end, over one hundred thousand men, or one in three, had deserted the Confederate Army, with Union desertion rates estimated at two hundred thousand men, or one in five. While Union desertions concentrated in the period just after the Emancipation Proclamation, most Confederate desertions occurred during the last eight months of the war.[1]

In any war, high rates of unauthorized departure had always signaled low levels of morale among troops, but during the Civil War, desertion took on new ideological meanings. Among Confederate troops, desertion frequently indicated class resentment. Poverty and unfair recruitment practices placed a heavy burden on yeomen who often found it necessary to return to their farms to take care of their families. Other Confederate soldiers left their posts to take advantage of Union amnesty agreements designed to weaken the Confederate Army. Desertion among Union troops was also ideologically motivated. The Emancipation Proclamation prompted the desertion of Union soldiers who felt the Union was now fighting for the “elevation of the negro race” and the “degradation of the white man.” Other Union soldiers believed President Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation had given excessive power to Congress at the expense of the states.[2]

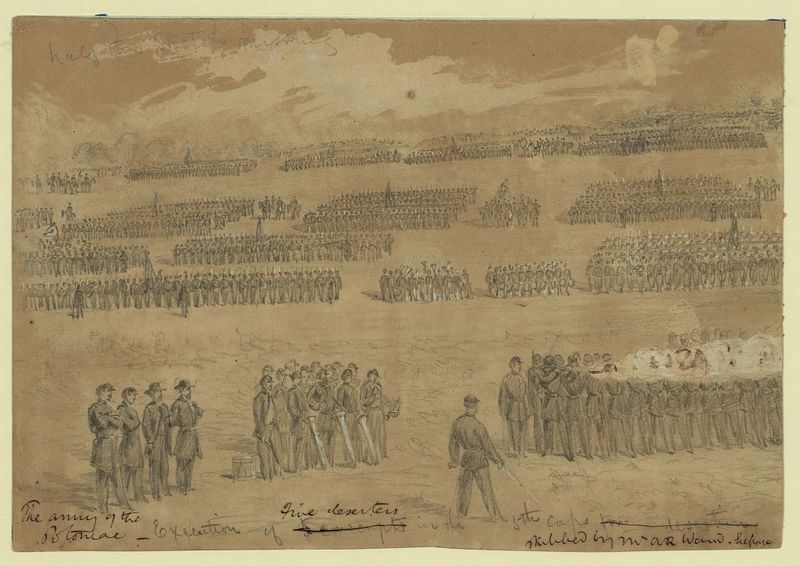

Punishment for desertion on both sides ranged from execution to branding captured soldiers on the hip with a “D.” Since neither side could afford to lose substantial numbers of men, executions were rare, with only 147 Union deserters executed during the course of the war. The few executions that did occur were often highly publicized affairs, as indicated in this engraved illustration published in the Illustrated London News on January 11, 1862, which depicts the execution of a deserter in a Union camp. Military officials frequently staged executions before an entire regiment in order to deter would-be deserters. The Union’s critical need for manpower ensured that these events happened infrequently. In addition, Lincoln worried that excessive public executions would damage public morale and divert crucial support from the war effort. Thus, it was more common for both armies to attempt to woo deserters back with offers of amnesty if they returned by a certain date.[3]

The number of soldiers lost to desertion often has a far greater effect on an army than its battlefield casualties. Desertion not only diminishes an army’s numbers, it also seriously undermines the resolve of the men who remain. During the Civil War, each side used desertion to deplete the other’s army and lower its morale. To encourage desertion among Union troops, the Confederacy offered Union soldiers sanctuary, civilian jobs, and land. The Union offered some Confederate deserters the opportunity to formally swear allegiance to the Union and then return to their homes. Other Confederate deserters remained in the North or West or entered the United States Army to serve on the western frontier. In addition to its impact on armies, desertion also affected civilians. The mountains of Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, and Kentucky, as well as areas of southeast Georgia, became known for harboring fugitives. In these areas large groups of former soldiers preyed on civilians, causing trouble for Union and Confederate military commanders for the duration of the war.”[4]

[1] Mark A. Weitz, A Higher Duty: Desertion Among Georgia Troops During the Civil War (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 2, 4; Ella Lonn, Desertion During the Civil War (1928; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 24-26; Mark A. Weitz, “Desertion,” Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social and Military History Ed. by David Stephen Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler (Santa Barbara, California: ABC CLIO, 2000), 593; Christopher Hamner, “Deserters in the Civil War,” National History Education Clearinghouse, accessed March 25, 2017, http://teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/23934; Weitz, “Preparing for the Prodigal Sons,” 106.

[2] Mark A. Weitz, “Preparing for the Prodigal Sons: The Development of the Union Desertion Policy During the Civil War,” Civil War History 45 no. 2 (June 1999): 99-100; Paul Escott, “Southern Yeomen and the Confederacy,” in South Atlantic Quarterly, 77, no. 2 (1978): 146-158; Weitz, “Preparing for the Prodigal Sons,” 106-07; Maj. Henry F. Kalfus of the Fifteenth Kentucky Volunteer Infantry, quoted in Jonathan W. White, Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014), 69.

[3] Hamner, “Deserters in the Civil War,”

[4] Weitz, “Desertion,” 593.