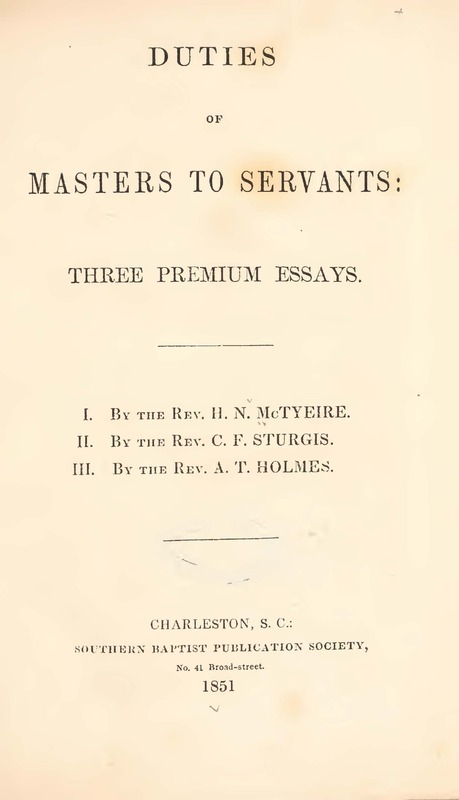

Title

Creator

Description

Source

Date

Text

When, at the formation of Eve, the God of the Universe declared, that it was not good for man to be alone, the importance of the social principle was fully recognized, and man became a social being. Founded upon the union thus originally instituted, certain relations are discovered to exist, in which are involved certain duties, each relation urging its claim respectively. Thus, the husband sustains a relation to his wife, the parent to his child, the citizen to his country, in each of which distinctive duties are to be discharged, growing out of the particular relation thus sustained. Among other relations which he sustains, man is master; and in this, as in all others, certain duties are involved. These relations are, all, of Divine appointment, (that between master and servant as positively as any other,) and, therefore, the duties which are involved, are all of Divine requirement. Every duty is a command, and god must be regarded as commanding the master to perform those duties to his servants, which the relation he bears to them involves and imposes....

Our present purpose is to inquire into the duties of masters, and, especially, of Christian masters, according to the word of God....

We infer, first, that the master should be the friend of his servant and that the servant should know it. Friendship implies good will, kindness, a desire for the welfare of him for whom it is entertained. Thus should the master feel towards his servant, and in the cultivation of this spirit and its decided manifestation, there need be no compromise of authority, no undue familiarity. The servant, under such a master, knows his condition, and understands that, while he is restricted to certain privileges and required to perform certain duties he is not held in subjection by an unfeeling tyrant, nor driven to his work by a heartless oppressor. A kind word, a pleasant look, a little arrangement for his comfort, assures him that there is one who cares for him; and, notwithstanding he goes forth to his daily labor, and toils at his daily task, his heart is light, his song is cheerful, and he seeks his humble couch at night, in the happy consciousness that his master is his friend. Such is the enviable lot of many servants in our “sunny South,” and on such plantations as feel the controlling influence of the master’s friendship for his servants, it may be noticed, as a general fact, that order is observed, peace is cultivated, mutual confidence and good will are encouraged, as much work is done as ought to be done, the sound of the last is but seldom heard, and the runaway’s punishment is but rarely inflicted. And yet, the friend becomes not the companion, and the effort on the part of the master to secure confidence and affection, affords no warrant for improper familiarity. The kind word and the pleasant look, are still the word and look of the master, and the little arrangements which are made for the servant’s comfort are made in full recognition of the relative positions occupied, and produce, on his part the grateful conviction that he is not regarded simply as property, but as a fellow being for whom feelings of kindness are cherished, and for whose happiness a proper desire is entertained.

Again, we infer, that the master should be the protector of his servant. The relation which they sustain to each other is that of superior and inferior, and while occasional circumstances may require that the master defend or vindicate his servant the obligations of every day call for his protection. The servant should feel that the superior wisdom, experience, power and authority of his master, constitute his abiding security. He should be encouraged to rely upon their certain and constant exercise, so that in regard to necessity, comfort, personal difficulty or danger, he may, confidently, look to his master for that protection which his particular case may demand. It is the master’s duty that such an understanding be established between himself and his servant. In view of the servant’s condition, it is both “just and equal,” and will contribute much towards securing that peace and mutual confidence which every good man loves to contemplate as the striking characteristic of his own family and household. Moreover, it will advance the master’s interest, for while no right is yielded, and no improper indulgence granted; while no authority is compromised, and no undue liberty allowed; at the same time, the servant learns to value his protection, loves his master, is attached to his home, and therefore less inclined to rove, dreads no separation from his family if he has one, and attends to his daily work, comparatively free from care and anxiety, and rejoicing in the assurance that, in his master, he has a kind, watchful and considerate protector.

Once more, we infer that the master should be the guide of his servant. In the duty here specified, reference is had, not only to the influence which the master is supposed to have over the movements or actions of his servant, but, also, to the superior intelligence of the master.

There is no relation, perhaps, unless it is that between father and son, in which a more decided influence is exerted, than that which exists between the master and his servant. Ordinary conduct and conversation are observed, manner is marked, habits are noticed, and, according as the master regulates his life by principles of right, his servant is influenced for good or for evil. The master may be a profane man, or a Sabbath breaker, or a drinker of ardent spirits – a licentious man in some positive sense – and, almost invariably, will his licentious course be acted out by those who are controlled, as well by his influence and example, as by his authority. That master speaks and acts thus, is not only a sufficient warrant with many servants, but, actually, a reason why they should speak and act thus themselves. And, are we accountable for the influence which we exert upon others? Will our common master in Heaven hold us responsible not only for the evil which we commit ourselves, but for that which we induce others to commit? Is there danger that I shall be confounded in the presence of the great Judge of all, and doubly confounded, because daring myself to profane the name of God, my servant feels at liberty to do the same? Masters! Christian masters! What manner of persons ought ye to be! Twenty, fifty, perhaps an hundred immortal, accountable beings look up to you, respectively; they watch your movements, they note your example, and they, almost literally, follow your guidance, as the traveler follows his guide through some unknown region. Whither does your influence lead them? In following our example, what prospect have they for peace with God beyond the grave? To what extent are they encouraged to pursue the right and avoid the wrong, by their regard for your good opinion, and their conviction that it can only be obtained by a correct and upright course of conduct?...

We infer, lastly, that the master should be the teacher of his servant. Ignorance, in a peculiar sense, attaches to the negro, and ignorance… is one principal cause of the want of virtue and of the immoralities which abound in the world. The law of the land, sustained by public opinion, and justified in view of the causes which require its existence and enforcement, denies to the servant the opportunity for instruction which might, otherwise, be afforded. As a very natural consequence, the servant independent of his constitutional tendency is, more or less, credulous and superstitious. He is constantly exposed to error, and especially error in regard to religious matters. It devolves, therefore, upon the master, in the discharge of his duty, to have respect to the ignorant condition of his servant, for ignorant, credulous and superstitious as he is, at the same time he is an immortal and accountable being.... It is urged, therefore, as an imperious duty, that the master, the Christian master, be the teacher of his servant. But teach him what, it may be asked? Teach him how to read and write? Instruct him in those branches of learning taught in our schools and colleges? Make him acquainted with those matters of general interest which agitate and disturb the political world? We answer, no; but teach him that he is a sinner, and that the Lord Jesus Christ is the sinner’s friend. Teach him the absolute necessity of repentance toward God, and faith in the crucified Redeemer. Teach him that he must deny himself all ungodliness and worldly lusts, and live soberly, and righteously, and godly, in this present world. Let the light of your superior knowledge shine upon the darkness of his ignorance, and let his credulity and superstition yield to that simplicity and godly sincerity, which the holy religion of the Son of God secures to all, masters and servants, who are brought to feel its sanctifying and saving power. Christian master, enter the dark cabin of thy servant, and with the lamp of truth in thy hand, light up his yet darker soul with the knowledge of him, whom to know is life eternal....

And now, Christian masters, suffer the word of exhortation from one, who, like yourselves, sustains this important relation. Lift your eyes to the judgment seat of Christ, remember your stewardship, consider the eternal welfare of your servants, and determine for yourselves, whether it is the part of wisdom to neglect this duty, or to make the proper effort, in order that it may be properly discharged. Anticipate that trying hour, when the smile or frown of your Maker and your Judge will depend upon the developments of that “Book of Remembrance,” wherein is registered your faithfulness or your neglect. Stand with your servants before His righteous throne, and let the convictions of that honest hour fix your purpose to meet the claims which your relation, as masters, imposes upon you, “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with they might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.” Ecc. Ix, 10.

Questions

- According to Holmes, why was slaveholding a Christian endeavor?

- What were the duties of Christian masters? What were the benefits of these duties?

- How would Holmes describe Christian slaves?

- How do you think David Walker, Frederick Douglass, or Harriet Jacobs would have responded to Holmes?