Title

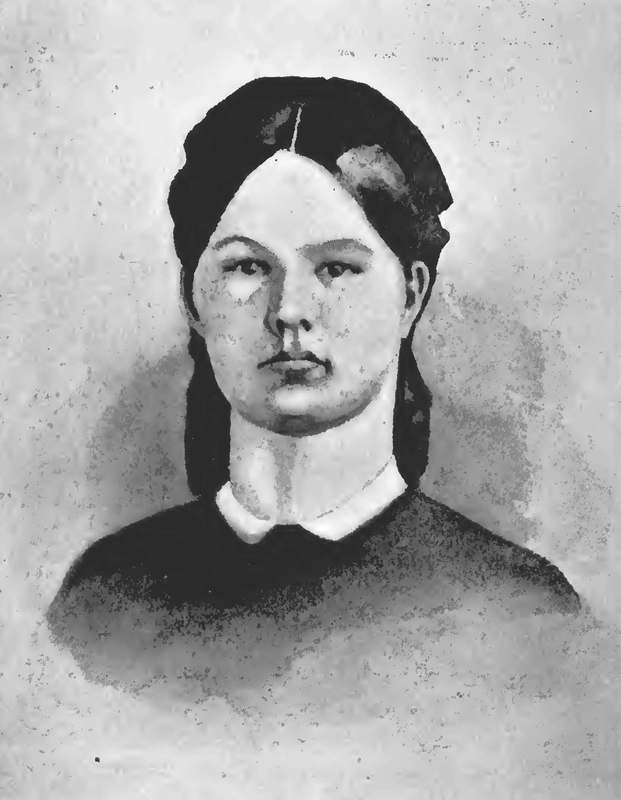

The Story of Mary Schwandt

Creator

Mary Schwandt-Schmidt

Description

Several Dakota Indians captured Mary Schwandt (later Schmidt), of a German farming family, then fourteen years old, near New Ulm, Minnesota, at the beginning of the Dakota War (1862). A Dakota woman named Snana (also called Maggie Good Thunder and later Maggie Brass) adopted Schwandt. After her release, Schwandt testified before a military commission about her experiences in captivity. Schwandt’s story first appeared in Bryant and Murch’s A History of the Great Massacre in 1864. After many years, Schwandt-Schmidt told a different version of her story in 1894 in the Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (excerpted here), focusing on Snana’s protection of her during her captivity. The two women renewed their acquaintance in 1894. (Snana also told her story for publication in the Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society in 1901.) Subsequently, Schwandt-Schmidt recorded additional versions of her narrative and spoke on her experiences.

Source

Kathryn Derounian-Stodola, The War in Words: Reading The Dakota Conflict through the Captivity Literature (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), xxv-xxvi; Mary Schwandt-Schmidt, “The Story of Mary Schwandt: Her Captivity During the Sioux ‘Outbreak,’ 1862,” Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society 6 (1894): 461–74.

Date

1894

Text

[Page 461] I was born in the district of Brandenburg, near Berlin, Germany, in March, 1848. My parents were John and Christina Schwandt. In 1858, when I was ten years of age, our family came to America and settled near Ripon, Wis. Here we lived about four years. In the early spring of 1862 we came to Minnesota and journeyed up the beautiful valley of the Minnesota river to above the mouth of Beaver creek and above where the town of Beaver Falls now stands, and somewhere near a small stream, which I think was called Honey creek, though it may have been known as Sacred Heart, my father took up a claim, built a house and settled.... [Page 462]

Our situation in our new home was comfortable, and my father seemed well satisfied. It was a little lonely, for our nearest white neighbors were some distance away.... We had no schools or churches, and did not see many white people, and we children were often lonesome and longed for companions. Just across the river, to the south of us, a few miles away, was the Indian village of the chief of Shakopee. The Indians visited us almost every day, but they were not company for us. Their ways were so strange that they were disagreeable to me. They were always begging, but otherwise were well behaved. We treated them kindly, and tried the best we knew to keep their good will. I remember well the first Indians we saw in Minnesota. It was near Fort Ridgely, when we were on our way into the country in our wagons. My sister, Mrs. Waltz, was much frightened at them. She cried and sobbed in her terror, and even hid herself in the wagon and would not look at them, so distressed was she. I have often wondered whether she did not then have a premonition of the dreadful fate she was destined to suffer at their cruel and brutal hands. In time I became accustomed to the Indians, and had no real fear of them.

About the 1st of August a Mr. Le Grand Davis came to our house in search of a girl to go to the house of Mr. J. B. Reynolds, who lived on the south side of the river on the bluff, just above the mouth of the Redwood, and assist Mrs. Reynolds in the housework. Mr. Reynolds lived on the main road, between the lower and Yellow Medicine agencies, and kept a sort of stopping place for travelers.... [Page 463] I could do most kinds of housework as well as many a young woman older than I, and I was so lonesome that I begged my mother to let me go and take the place. She and all the rest of the family were opposed to my going, but I insisted, and at last they let me have my way.... How little did I think, as I rode away from home, that I should not see it again, and that in less than a month of all that peaceful and happy household but one of its members my dear, brave brother August should be left to me.... [Page 464]

I do not now recall anything of special importance that occurred during my stay here until the dreadful morning of the outbreak.... The morning of Aug. 18 came.... A wagon drove up from the west, in which were a Mr. Patoile, a trader, and another Frenchman from the Yellow Medicine agency, where Mr. Patoile's store was. They stopped for breakfast. While they were eating, a half-breed, named Antoine La Blaugh, who was living with John Mooer, another half-breed, not far away, came to the house and told Mr. Reynolds that Mr. Mooer had sent him to tell us that the Indians had broken out and had gone down to the lower agency, ten miles below, and across the river to the Beaver creek settlements to murder all the whites!...

[Page 465] The dreadful intelligence soon reached us girls, and we at once made preparations to fly. Mr. Patoile agreed to help us.... I have often honestly and earnestly tried hard to forget all about that dreadful time, and only those recollections that I cannot put away, or that are not painful in their nature, remain in my memory.... [Page 466] When we were within about eight miles of New Ulm and thought all serious danger was over, we met about fifty Indians coming from the direction of the town. They were mounted, and had wagons loaded with flour and all sorts of provisions and goods taken from the houses of the settlers. They were nearly naked, painted all over their bodies, and all of them seemed to be drunk, shouting and yelling and acting very riotously in every way. Two of them dashed forward to [Page 467] us, one on each side of the wagon, and ordered us to halt. Mr. Patoile turned the wagon to one side of the road, and all of us jumped out except him.... I was running as fast as I could towards the slough, when two Indians caught me, one by each of my arms, and stopped me. An Indian caught Mattie Williams and tore off part of her "shaker" bonnet. Then another came, and the two led her back to the wagon. I was led back also. Mary Anderson was probably carried back. Mattie was put in a wagon with Mary, and I was placed in one driven by the negro Godfrey.

[Page 468] About 5 o'clock we started in the direction of the lower agency. Three hours later we arrived at the house of the chief, Wacouta, in his village, half a mile or so below the agency. Here I found Mrs. De Camp (now Mrs. Sweet), whose story was published in the Pioneer Press of July 15. As she has so well described the incidents of that dreadful night and the four following dreadful days, it seems unnecessary that I should repeat them; and, indeed, it is a relief to avoid the subject. Since it pleased God that we should all suffer as we did at this time, I pray him of his mercy to grant that all my memories of this period of my captivity may soon and forever pass away.... On the fourth day we were taken from Wacouta's, up to Little Crow's village, two miles above the agency. Mary Ander-son died at 4 o'clock the following morning.

[Page 469] Mrs. Huggan, the half-breed woman whose experience as a prisoner has been printed in this paper, says she remembers me at this time, and that my eyes were always red and swollen from constant weeping. I presume this is true. But soon there came a time when I did not weep. I could not. The dreadful scenes I had witnessed, the sufferings that I had undergone, the almost certainty that my family had all been killed, and that I was alone in the world, and the belief that I was destined to witness other things as horrible as those I had seen, and that my career of suffering and misery had only begun, all came to my comprehension, and when I realized my utterly wretched, helpless and hopeless situation, for I did not think I would ever be released, I became as one paralyzed, and could hardly speak. Others of my fellow captives say they often spoke to me, but that I said but little, and went about like a sleep-walker....

[Page 470] But now it pleased Providence to consider that my measure of suffering was nearly full. An old Indian woman called Wam-nu-ka-win (meaning a peculiarly shaped bead called barley corn, sometimes used to produce the sound in Indian rattles) took compassion on me and bought me of the Indian who claimed me, giving a pony for me. She gave me to her daughter, whose Indian name was Snana (ringing sound), but the whites called her Maggie, and who was the wife of Wa-kin-yan Weste, or Good Thunder.... Maggie and her mother were both very kind to me, and Maggie could not have treated me more tenderly if I had been her daughter. Often and often [Page 471] she preserved me from danger, and sometimes, I think, she saved my life. Many a time, when the savage and brutal Indians were threatening to kill all the prisoners, and it was feared they would, she and her mother hid me, piling blankets and buffalo robes upon me until I would be nearly smothered, and then they would tell everybody that I had left them.... [W]herever you are, Maggie, I want you to know that the little captive German girl you so often befriended and shielded from harm loves you still for your kindness and care, and she prays God to bless you and reward you in this life and that to come. I was told to call Mr. Good Thunder and Maggie "father" and "mother," and I did so. It was best, for then some of the Indians seemed to think I had been adopted into the tribe....

[Page 472] I think we remained at Little Crow's village about a week, when we moved in haste up toward Yellow Medicine about fifteen miles and encamped.... We were encamped at Yellow Medicine at least two weeks. Then we left and went on west, making so many removals that I cannot remember them... During my captivity I saw very many dreadful scenes and sickening sights, but I need not describe them....

I remember Mrs. Dr. Wakefield and Mrs. [Page 473] Adams. They were painted and decorated and dressed in full Indian costume, and seemed proud of it. They were usually in good spirits, laughing and joking, and appeared to enjoy their new life. The rest of us disliked their conduct, and would have but little to do with them. Mrs. Adams was a handsome young woman, talented and educated, but she told me she saw her husband murdered, and that the Indian she was then living with had dashed out her baby's brains before her eyes. And yet she seemed perfectly happy and contented with him!

At last came Camp Release and our deliverance by the soldiers under Gen. Sibley....

I was taken below to St. Peter, where I learned the particulars of the sad fate of my family. I must be excused from giving the particulars of their atrocious murders. All were murdered at our home but my brother August. His head was split with a tomahawk, and he was left senseless for dead, but he recovered consciousness, and finally, though he was but ten years of age, succeeded in escaping to Fort Ridgely.... Soon after arriving at St. Peter I was sent to my friends and relatives in Wisconsin, and here I met my brother August.

[Page 474] Life is made up of shadow and shine. I sometimes think I have had more than my share of sorrow and suffering, but I bear in mind that I have seen much of the agreeable side of life, too. A third of a century almost has passed since the period of my great bereavement and of my captivity. The memory of that period, with all its hideous features, often rises before me, but I put it down. I have called it up at this time because kind friends have assured me that my experience is a part of a leading incident in the history of Minnesota that ought to be given to the world. In the hope that what I have written may serve to inform the present and future generations what some of the pioneers of Minnesota underwent in their efforts to settle and civilize our great state, I submit my plain and imperfect story.

Mary Schwandt-Schmidt

St. Paul, July 26, 1894

Our situation in our new home was comfortable, and my father seemed well satisfied. It was a little lonely, for our nearest white neighbors were some distance away.... We had no schools or churches, and did not see many white people, and we children were often lonesome and longed for companions. Just across the river, to the south of us, a few miles away, was the Indian village of the chief of Shakopee. The Indians visited us almost every day, but they were not company for us. Their ways were so strange that they were disagreeable to me. They were always begging, but otherwise were well behaved. We treated them kindly, and tried the best we knew to keep their good will. I remember well the first Indians we saw in Minnesota. It was near Fort Ridgely, when we were on our way into the country in our wagons. My sister, Mrs. Waltz, was much frightened at them. She cried and sobbed in her terror, and even hid herself in the wagon and would not look at them, so distressed was she. I have often wondered whether she did not then have a premonition of the dreadful fate she was destined to suffer at their cruel and brutal hands. In time I became accustomed to the Indians, and had no real fear of them.

About the 1st of August a Mr. Le Grand Davis came to our house in search of a girl to go to the house of Mr. J. B. Reynolds, who lived on the south side of the river on the bluff, just above the mouth of the Redwood, and assist Mrs. Reynolds in the housework. Mr. Reynolds lived on the main road, between the lower and Yellow Medicine agencies, and kept a sort of stopping place for travelers.... [Page 463] I could do most kinds of housework as well as many a young woman older than I, and I was so lonesome that I begged my mother to let me go and take the place. She and all the rest of the family were opposed to my going, but I insisted, and at last they let me have my way.... How little did I think, as I rode away from home, that I should not see it again, and that in less than a month of all that peaceful and happy household but one of its members my dear, brave brother August should be left to me.... [Page 464]

I do not now recall anything of special importance that occurred during my stay here until the dreadful morning of the outbreak.... The morning of Aug. 18 came.... A wagon drove up from the west, in which were a Mr. Patoile, a trader, and another Frenchman from the Yellow Medicine agency, where Mr. Patoile's store was. They stopped for breakfast. While they were eating, a half-breed, named Antoine La Blaugh, who was living with John Mooer, another half-breed, not far away, came to the house and told Mr. Reynolds that Mr. Mooer had sent him to tell us that the Indians had broken out and had gone down to the lower agency, ten miles below, and across the river to the Beaver creek settlements to murder all the whites!...

[Page 465] The dreadful intelligence soon reached us girls, and we at once made preparations to fly. Mr. Patoile agreed to help us.... I have often honestly and earnestly tried hard to forget all about that dreadful time, and only those recollections that I cannot put away, or that are not painful in their nature, remain in my memory.... [Page 466] When we were within about eight miles of New Ulm and thought all serious danger was over, we met about fifty Indians coming from the direction of the town. They were mounted, and had wagons loaded with flour and all sorts of provisions and goods taken from the houses of the settlers. They were nearly naked, painted all over their bodies, and all of them seemed to be drunk, shouting and yelling and acting very riotously in every way. Two of them dashed forward to [Page 467] us, one on each side of the wagon, and ordered us to halt. Mr. Patoile turned the wagon to one side of the road, and all of us jumped out except him.... I was running as fast as I could towards the slough, when two Indians caught me, one by each of my arms, and stopped me. An Indian caught Mattie Williams and tore off part of her "shaker" bonnet. Then another came, and the two led her back to the wagon. I was led back also. Mary Anderson was probably carried back. Mattie was put in a wagon with Mary, and I was placed in one driven by the negro Godfrey.

[Page 468] About 5 o'clock we started in the direction of the lower agency. Three hours later we arrived at the house of the chief, Wacouta, in his village, half a mile or so below the agency. Here I found Mrs. De Camp (now Mrs. Sweet), whose story was published in the Pioneer Press of July 15. As she has so well described the incidents of that dreadful night and the four following dreadful days, it seems unnecessary that I should repeat them; and, indeed, it is a relief to avoid the subject. Since it pleased God that we should all suffer as we did at this time, I pray him of his mercy to grant that all my memories of this period of my captivity may soon and forever pass away.... On the fourth day we were taken from Wacouta's, up to Little Crow's village, two miles above the agency. Mary Ander-son died at 4 o'clock the following morning.

[Page 469] Mrs. Huggan, the half-breed woman whose experience as a prisoner has been printed in this paper, says she remembers me at this time, and that my eyes were always red and swollen from constant weeping. I presume this is true. But soon there came a time when I did not weep. I could not. The dreadful scenes I had witnessed, the sufferings that I had undergone, the almost certainty that my family had all been killed, and that I was alone in the world, and the belief that I was destined to witness other things as horrible as those I had seen, and that my career of suffering and misery had only begun, all came to my comprehension, and when I realized my utterly wretched, helpless and hopeless situation, for I did not think I would ever be released, I became as one paralyzed, and could hardly speak. Others of my fellow captives say they often spoke to me, but that I said but little, and went about like a sleep-walker....

[Page 470] But now it pleased Providence to consider that my measure of suffering was nearly full. An old Indian woman called Wam-nu-ka-win (meaning a peculiarly shaped bead called barley corn, sometimes used to produce the sound in Indian rattles) took compassion on me and bought me of the Indian who claimed me, giving a pony for me. She gave me to her daughter, whose Indian name was Snana (ringing sound), but the whites called her Maggie, and who was the wife of Wa-kin-yan Weste, or Good Thunder.... Maggie and her mother were both very kind to me, and Maggie could not have treated me more tenderly if I had been her daughter. Often and often [Page 471] she preserved me from danger, and sometimes, I think, she saved my life. Many a time, when the savage and brutal Indians were threatening to kill all the prisoners, and it was feared they would, she and her mother hid me, piling blankets and buffalo robes upon me until I would be nearly smothered, and then they would tell everybody that I had left them.... [W]herever you are, Maggie, I want you to know that the little captive German girl you so often befriended and shielded from harm loves you still for your kindness and care, and she prays God to bless you and reward you in this life and that to come. I was told to call Mr. Good Thunder and Maggie "father" and "mother," and I did so. It was best, for then some of the Indians seemed to think I had been adopted into the tribe....

[Page 472] I think we remained at Little Crow's village about a week, when we moved in haste up toward Yellow Medicine about fifteen miles and encamped.... We were encamped at Yellow Medicine at least two weeks. Then we left and went on west, making so many removals that I cannot remember them... During my captivity I saw very many dreadful scenes and sickening sights, but I need not describe them....

I remember Mrs. Dr. Wakefield and Mrs. [Page 473] Adams. They were painted and decorated and dressed in full Indian costume, and seemed proud of it. They were usually in good spirits, laughing and joking, and appeared to enjoy their new life. The rest of us disliked their conduct, and would have but little to do with them. Mrs. Adams was a handsome young woman, talented and educated, but she told me she saw her husband murdered, and that the Indian she was then living with had dashed out her baby's brains before her eyes. And yet she seemed perfectly happy and contented with him!

At last came Camp Release and our deliverance by the soldiers under Gen. Sibley....

I was taken below to St. Peter, where I learned the particulars of the sad fate of my family. I must be excused from giving the particulars of their atrocious murders. All were murdered at our home but my brother August. His head was split with a tomahawk, and he was left senseless for dead, but he recovered consciousness, and finally, though he was but ten years of age, succeeded in escaping to Fort Ridgely.... Soon after arriving at St. Peter I was sent to my friends and relatives in Wisconsin, and here I met my brother August.

[Page 474] Life is made up of shadow and shine. I sometimes think I have had more than my share of sorrow and suffering, but I bear in mind that I have seen much of the agreeable side of life, too. A third of a century almost has passed since the period of my great bereavement and of my captivity. The memory of that period, with all its hideous features, often rises before me, but I put it down. I have called it up at this time because kind friends have assured me that my experience is a part of a leading incident in the history of Minnesota that ought to be given to the world. In the hope that what I have written may serve to inform the present and future generations what some of the pioneers of Minnesota underwent in their efforts to settle and civilize our great state, I submit my plain and imperfect story.

Mary Schwandt-Schmidt

St. Paul, July 26, 1894