Title

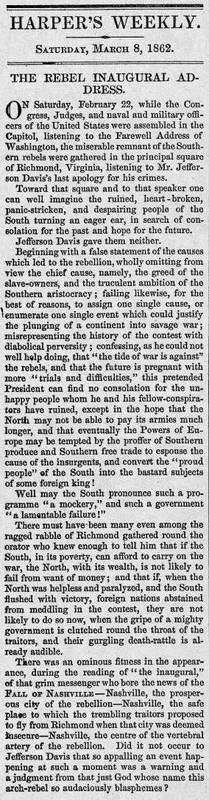

The Rebel Inaugural Address

Creator

Harper's Weekly

Source

"The Rebel Inaugural Address," Harper's Weekly, March 8, 1862.

Date

1862-03-08

Coverage

Richmond, Virginia

Text

ON Saturday, February 22, while the Congress, Judges, and naval and military officers of the United States were assembled in the Capitol, listening to the Farewell Address of Washington, the miserable remnant of the Southern rebels were gathered in the principal square of Richmond, Virginia, listening to Mr. Jefferson Davis's last apology for his crimes.

Toward that square and to that speaker one can well imagine the ruined, heart-broken, panic-stricken, and despairing people of the South turning an eager ear, in search of consolation for the past and hope for the future.

Jefferson Davis gave them neither.

Beginning with a false statement of the causes which led to the rebellion, wholly omitting from view the chief cause, namely, the greed of the slave-owners, and the truculent ambition of the Southern aristocracy; failing likewise, for the best of reasons, to assign one single cause, or enumerate one single event which could justify the plunging of a continent into savage war; misrepresenting the history of the contest with diabolical perversity; confessing, as he could not well help doing, that “the tide of war is against” the rebels, and that the future is pregnant with more “trials and difficulties,” this pretended President can find no consolation for the unhappy people whom he and his fellow-conspirators have ruined, except in the hope that the North may not be able to pay its armies much longer, and that eventually the Powers of Europe may be tempted by the proffer of Southern produce and Southern free trade to espouse the cause of the insurgents, and convert the “proud people” of the South into the bastard subjects of some foreign king!

Well may the South pronounce such a programme “a mockery,” and such a government “a lamentable failure!”

There must have been many even among the ragged rabble of Richmond gathered round the orator who knew enough to tell him that if the South, in its poverty, can afford to carry on the war, the North, with its wealth, is not likely to fail from want of money; and that if, when the North was helpless and paralyzed, and the South flushed with victory, foreign nations abstained from meddling in the contest, they are not likely to do so now, when the gripe of a mighty government is clutched round the throat of the traitors, and their gurgling death-rattle is already audible.

There was an ominous fitness in the appearance, during the reading of “the inaugural,” of that grim messenger who bore the news of the Fall of Nashville—Nashville, the prosperous city of the rebellion—Nashville, the safe place to which the trembling traitors proposed to fly from Richmond when that city was deemed insecure—Nashville, the centre of the vertebral artery of the rebellion. Did it not occur to Jefferson Davis that so appalling an event happening at such a moment was a warning and a judgment from that just God whose name this arch-rebel so audaciously blasphemes?

Toward that square and to that speaker one can well imagine the ruined, heart-broken, panic-stricken, and despairing people of the South turning an eager ear, in search of consolation for the past and hope for the future.

Jefferson Davis gave them neither.

Beginning with a false statement of the causes which led to the rebellion, wholly omitting from view the chief cause, namely, the greed of the slave-owners, and the truculent ambition of the Southern aristocracy; failing likewise, for the best of reasons, to assign one single cause, or enumerate one single event which could justify the plunging of a continent into savage war; misrepresenting the history of the contest with diabolical perversity; confessing, as he could not well help doing, that “the tide of war is against” the rebels, and that the future is pregnant with more “trials and difficulties,” this pretended President can find no consolation for the unhappy people whom he and his fellow-conspirators have ruined, except in the hope that the North may not be able to pay its armies much longer, and that eventually the Powers of Europe may be tempted by the proffer of Southern produce and Southern free trade to espouse the cause of the insurgents, and convert the “proud people” of the South into the bastard subjects of some foreign king!

Well may the South pronounce such a programme “a mockery,” and such a government “a lamentable failure!”

There must have been many even among the ragged rabble of Richmond gathered round the orator who knew enough to tell him that if the South, in its poverty, can afford to carry on the war, the North, with its wealth, is not likely to fail from want of money; and that if, when the North was helpless and paralyzed, and the South flushed with victory, foreign nations abstained from meddling in the contest, they are not likely to do so now, when the gripe of a mighty government is clutched round the throat of the traitors, and their gurgling death-rattle is already audible.

There was an ominous fitness in the appearance, during the reading of “the inaugural,” of that grim messenger who bore the news of the Fall of Nashville—Nashville, the prosperous city of the rebellion—Nashville, the safe place to which the trembling traitors proposed to fly from Richmond when that city was deemed insecure—Nashville, the centre of the vertebral artery of the rebellion. Did it not occur to Jefferson Davis that so appalling an event happening at such a moment was a warning and a judgment from that just God whose name this arch-rebel so audaciously blasphemes?